During the second week of the month of July 2023, I had the privilege of participating in a unique field course. As a Master's student at the University of Victoria, I accompanied a wide range of students and educators along with survivors and families who were impacted by the Canadian government's policy of interning anyone of Japanese descent following the bombing of Pearl Harbour. The government used the bombing at Pearl Harbour as an excuse to execute racist and dehumanizing policies on its own citizens.

What follows is an expansion of the photo journal I created over the course of this week on the road.

(RE)BUILDING COMMUNITY GROUNDED IN 'SHIKATA GA NAI'

On the tour of the sites related to Japanese Canadian incarceration, the concepts of community, identity and memorialization were constantly engaging with each other. In discussing the different attitudes towards incarceration of different generations of Japanese Canadians, the phrase ‘Shikata ga nai’ came up again and again. ‘Shikata ga nai’ or ‘it cannot be helped’ brought these three concepts together. Through the mentality of ‘it cannot be helped,’ Japanese Canadians have been forced to reframe their understandings of themselves, their place, and their country. Over the course of this tour, I experienced community building with a community to which I had previously been a stranger. However, in the closing comments as our bus made its way to back to Burnaby where the bus had originally picked us up, the relationships that had grown from the vulnerability of individuals and physically visiting the sites felt more akin to family. Although we cannot do anything about changing the past, we can create community resilience through relationships and vulnerability.

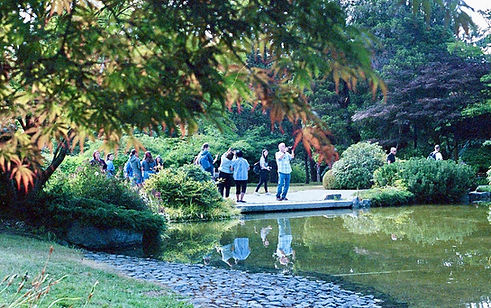

MOMIJI GARDENS, HASTINGS PARK, VANCOUVER

As our first stop of the whole tour at Hastings Park, and the first stop within the Park, the Momiji Gardens set the stage of acknowledging the harm perpetrated onto Japanese Canadians through both changing the landscape to honour those harmed and of preserving the sites as they are. Both makes visitors consider Japanese Canadian incarceration and dispossession in different ways.

On the sign directly outside the entrance to the Gardens, ‘Momiji’ is translated simply as ‘Maple’, which Michael Abe remarked was only partially accurate, and would be more accurately translated as ‘Japanese Maple.’

Previously named Fourteen Mile Ranch near Hope, BC. Tashme was renamed by the British Columbia Security Commission after: Austin Taylor (a Vancouver businessman), John Shirras ( BC provincial police) and Frederick Mead (RCMP).

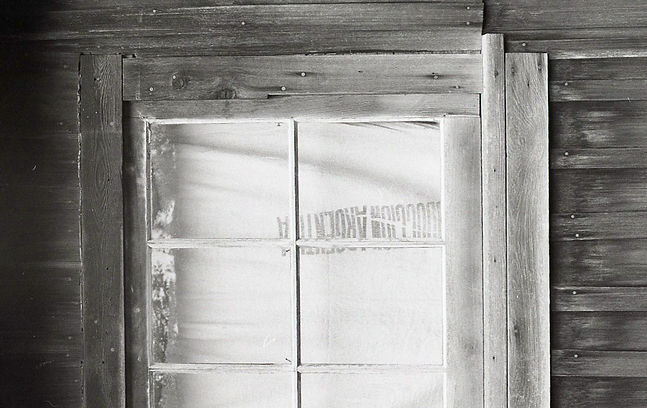

TASHME: TAylor SHirras and MEad

In Tashme, signs of the Japanese Canadians creating a life within the confines of incarceration are everywhere. We heard about sheltering children from the extremely poor living conditions through continuing community programs inside the camps, such as the Scouts. Prioritizing non-essential items such as clothing can be seen to represent the need to preserve a sense of normalcy. This extended into hiding and bettering the poor construction of the shacks they were forced to inhabit, the Japanese Canadians used tar paper in an attempt to weatherproof and insulate their shacks.

NIKKEI LEGACY PARK, GREENWOOD

The Nikkei Legacy Park’s flag post includes 3 Koinobori along with a Canadian Flag. The streamers are a symbol of Japanese culture, with their historical and cultural significance being tied to Tango no sekku, which has its origins in warding off evil spirits and celebrating children’s happiness.

Seen at many sites we visited, I interpreted the significance of pairing the Koinobori and the Canadian flag as an assertion of a Japanese Canadian identity that was not recognized during the incarceration of Japanese Canadians. Furthermore, the cultural significance of the Koinobori can be interpreted to specifically reference and honour the impact of incarceration on Japanese Canadian children.

GREENWOOD

CHRISTINA LAKE

At Christina Lake, there was an acknowledgement amongst the group that the narrative being put forward by our host and guide was an idealized one. The majority of discussions surrounding this topic were grounded in recognition of this idealism. On our walk, I approached a local resident who was washing her car and struck up a conversation. Quickly, this woman brought out a book on the local history of interment and discussed how the community currently living in Christina Lake were still active on researching and learning this history. Community relationships can happen between past and present inhabitants and with residents and visitors.

LEMON CREEK

NIKKEI INTERNMENT MEMORIAL CENTRE

In this picture, we see a bag of rice repurposed as a curtain. Many survivors and descendants of those who were incarcerated in the camps spoke of the mentality of not letting anything go to waste. This developed as a result of the poverty imposed by the Canadian government and carried on by the Japanese Canadian community as a result of the trauma of incarceration. Although bags of rice were used in multiple ways, access to rice shows the value and comfort that came from preparing Japanese food. This is further exemplified by the presence of Fuki in the vegetable garden at NIMC but also in Tashme.

SANDON

EAST LILLOOET MEMORIAL GARDEN

In the Memorial Garden in East Lillooet, sisters Sandra and Tobi, descendants of those who were interned scratch over to make a copy of the name of a relative etched into a stone. Joyce, who is in the foreground, jumps in to help hold the paper in place. As these sisters are taking a piece of the memorial to bring home with them, a large part of the tour group gathers to watch. Witnessing this, we recognize the significance of this act for these sisters, the loss and harm inflicted by incarceration onto this family, the memorialization of incarceration in this stone, but also of these individuals by writing their names into stone. As witnesses, we become a collective and further grasp how personal incarceration was.

MIYAZAKI HOUSE